Abstract: In thermal management design, fan speed is often mistaken as a direct indicator of cooling performance. This article demystifies the essence of heat dissipation, clarifying the non-linear relationship between fan speed, airflow, static pressure, and system efficiency. It highlights the potential pitfalls and trade-offs of blindly pursuing high RPM, providing engineers and decision-makers with a more holistic perspective for component selection.

Introduction: A Pervasive Cognitive Bias

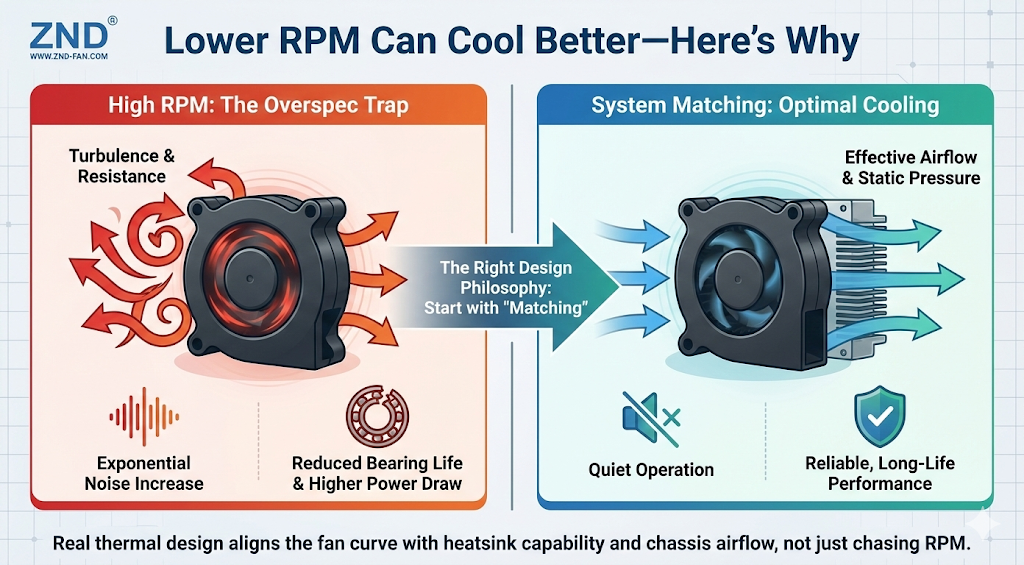

“To improve cooling, specify a fan with higher RPM.” This might be one of the most common suggestions in electronics thermal design. However, this seemingly intuitive conclusion overlooks a critical fact: thermal management is a systemic challenge, where final efficacy is determined by the weakest link in the chain, not just the fan alone.

This article explores why the relationship between rotational speed and cooling effectiveness is not a simple linear correlation and reveals the core logic that matters more than chasing maximum RPM in thermal design.

Part 1: Core Logic – The Essence of Cooling is “Effective Heat Transfer”

The primary mission of a cooling fan is to create forced convection, efficiently transferring heat from surfaces like heatsink fins or chip casings into the air. Therefore, the true metrics defining cooling performance are the “volume of cool air effectively utilized per unit of time.”

This depends on two interrelated engineering parameters:

- Airflow (CFM/m³/h): The total volume of air moved by the fan per unit of time, determining “how much air participates in heat exchange.”

- Static Pressure (mmH₂O/inH₂O): The fan’s ability to overcome system resistance (e.g., dense fins, filters, duct bends), determining “whether air can effectively penetrate the heat exchange interface.”

RPM is merely one driving factor influencing airflow and pressure, and its impact is strictly constrained by the fan’s own aerodynamic design (blade shape, count, angle, etc.). Simplifying cooling performance to an RPM race is akin to judging a vehicle’s load capacity and off-road prowess solely by its “engine speed,” neglecting the critical roles of the transmission, tires, and chassis tuning.

Part 2: The “Non-Linear” Relationship Between RPM and Efficacy – Understanding the Performance Cliff

At lower RPM ranges, increasing speed typically leads to significant improvements in both airflow and static pressure, resulting in noticeable cooling gains. However, as RPM continues to climb, the system gradually approaches and surpasses a performance cliff, where “diminishing returns” become stark:

- Declining Aerodynamic Efficiency: High-velocity airflow within narrow, complex heatsink fin channels tends to generate severe turbulence and vortices. These chaotic flows not only fail to smoothly carry heat away but can form “air barriers,” significantly increasing flow resistance and stalling the growth of actual airflow available for effective heat exchange.

- System Imbalance: If the thermal module itself has bottlenecked heat transfer capability (e.g., heat pipe efficiency, vapor chamber area, fin conductivity), heat cannot be quickly transferred to the air-contact surface. At this point, even the highest fan RPM is like blowing air against a hot wall, unable to improve the core heat transfer efficiency.

- Motor Operation Deviates from Peak Efficiency: Fan motors have an optimal power-RPM operating point for maximum efficiency. Beyond this range, more electrical energy converts into coil heat and mechanical friction loss rather than driving airflow, inadvertently adding extra thermal load to the system.

Part 3: The Hidden Cost of High RPM – Trade-offs That Cannot Be Ignored

Even ignoring the attenuation of cooling gains, the comprehensive cost brought by high RPM often makes it “counterproductive” in most application scenarios:

- Exponential Noise Increase: Fan noise is proportional to the 5th to 7th power of RPM. Doubling the speed can increase sound pressure level by over 15 dB, which is devastating for user experience in consumer products (like laptops, appliances) and unacceptable in quiet environments (e.g., medical, office settings).

- Compromised Reliability & Lifespan: Bearing wear (for both ball and sleeve types) is highly correlated with speed and operating temperature. Sustained high-RPM operation drastically reduces the fan’s MTTF (Mean Time To Failure), impacting end-product longevity, reputation, and maintenance costs.

- Power Consumption & Thermal Management Conflict: Fan power consumption increases with the cube of RPM. In battery-powered devices or systems with strict efficiency requirements, a high-RPM fan can become a “power hog,” and its self-generated heat can complicate the internal thermal environment.

Part 4: The Right Design Philosophy – Start with “Matching,” Aim for System Optimization

Excellent thermal design begins with understanding the entire heat path and ends with the precise matching of all components. The correct sequence of thinking should be:

- Define Thermal Requirements: Clarify the device’s maximum thermal design power (TDP), allowable temperature rise, and acoustic limits.

- Optimize the Thermal Module: Prioritize designing or selecting a heatsink (including heat pipes, vapor chambers, fins) with high thermal conductivity and sufficient heat capacity.

- Design an Efficient Airflow Path: Ensure unobstructed intake and that airflow is directed smoothly past key heat sources.

- Select the Fan Scientifically: Based on the system impedance curve, choose a fan that operates smoothly, efficiently, and quietly near the target operating point (required airflow and pressure). Here, RPM is merely a derived result, not the primary target.

The Value ZND Brings: As a professional supplier with a deep understanding of thermal system synergy, we not only offer an extensive range of fan products but can also assist customers with early-stage airflow analysis and fan selection to avoid the “RPM-only” trap. Our expertise in bearing technology, motor control, and aerodynamic design is dedicated to delivering superior airflow performance and reliability across a wider RPM range, achieving the optimal balance of cooling efficiency, acoustic performance, and product lifespan.

Conclusion: Returning to Fundamentals – The Wise Pursue Efficacy

The efficacy of a cooling fan is never defined solely by the number on a tachometer. It represents a complex balance involving fluid dynamics, heat transfer, acoustics, and reliability.

High RPM is one possible means to achieve efficient cooling, but it is never the end goal, nor is it the only path. Discerning engineers understand: The best solution is the one that optimizes total system cost (performance, noise, lifespan, power consumption) while meeting the thermal requirements.